This article, published here with the writer’s kind permission, is from Clarion, April 26 2024. It is relevant to FRSA readers, since we share the same historical roots with our Canadian sister churches. JN

The doctrine concerning the church – known as “ecclesiology” (nice big word!) has a colourful development in the early history of the Canadian Reformed Churches (CanRC). In two brief articles, I’d like to trace some aspects of that development. The trigger for presenting this material at this time is the fact that 2024 represents the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of 1944, an event in which the doctrine concerning the church played a pivotal role. In fact, the events of the Liberation served as a crucible which formed the church-thinking of so many immigrants. That thinking in turn explains to large degree why the CanRC came into existence and how they conducted themselves in their (early) years.

To kick open the door of this discussion consider this: the immigrants’ church-thinking meant they actively sought not to add another federation of churches to the existing ecclesiastical mosaic of their new homeland but sought instead to join in the Lord’s existing church-gathering work. It can only do us good to know our own history – lest we repeat its mistakes. The story begins with understanding the work of Prof. Dr. Klaas Schilder.

BACKGROUND

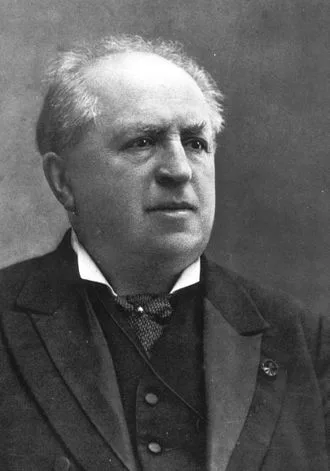

Klaas Schilder (born 1890) rose to prominence in the Netherlands in the decade after Abraham Kuyper died (1920). In the years after his death, Kuyper’s students attempted to elevate their master’s teachings in the areas of politics and religion as the final word on a given matter. In my years of ministry, I’ve heard from multiple people who attended catechism classes in the 1930’s that Kuyper’s books formed the authority in the catechism class, even beyond the Heidelberg Catechism itself. For many in that time period, Kuyper’s distinctive and his explanation of a given Bible passage amounted to the final word.

Schilder (amongst others) dared to offer criticism on some of the things Kuyper taught. To be clear: Schilder had very high regard for Abraham Kuyper and esteemed him as a gracious gift from God who contributed much good to his country and the church. But, like every other sinner, Kuyper didn’t get everything right. As forces within the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands worked to establish Kuyper’s words as final on some issue, Schilder dug into Scripture (with the assistance of writers in the course of church history) to expose weaknesses he spotted in Kuyper and offer a better insight. He used his position as contributor (and later editor) of De Reformatie (a weekly publication within the churches) to show where Kuyper was correct and where he stood to be corrected. Four years ago Clarion published an article in which I paid attention to Kuyper’s teaching on Presumptive Regeneration. [i] This time I choose to draw attention to elements of his teaching on the church.

KUYPER ON CHURCH

Kuyper taught much about the church that remains highly valuable for us today (I think, for example, of his book on liturgy [ii] and the positions he took in relation to church government). In his overarching view on the church, however, he gave place to philosophical concepts rooted in pre-Christian Greek philosophy. In keeping with distinctions he learned from Plato, Kuyper spoke of the church as it exists in the mind of God (which he called the invisible church) and as we see it (that’s the visible church). The invisible church is the real thing, consisting of all the elect around the globe of past, present, and future. The visible church is the numerous manifestations of this invisible church in our towns and countries, of which one church is a more pure (or less pure) expression of the real church as God sees it. This is the doctrine of pluriformity. As each flower in your garden may be celebrated because of how it contributes its own beauty to the garden, so each church in town may be celebrated for what it adds to the town’s ecclesiastical garden (this is Kuyper’s analogy). So Kuyper declined to term the church from which he broke away in the Doleantie of 1886 a false church as it was simply another flower in the garden. He did, though, feel that his own church (the Reformed Churches of the Netherlands) was the most pure manifestation of the church as God sees it and that this church was duty bound to try to bring surrounding churches to better understandings of the various doctrines of Scripture. Though it was preferable that Christians join a church (particularly the purest, i.e., the RCN), at bottom your responsibility was to ensure that you belonged to the invisible church, i.e., that you were a believer.

Coupled closely to this concept of invisible/visible was the distinction Kuyper made between the church as organism and the church as institution. The church as organism was the church as God sees it, carrying out its function in daily life. This involves believers speaking and acting as Christians in their daily activities and so growing the gospel in all society. The church as institution referred to that which met each Sunday, had office bearers, confessions, and perhaps a building. The organism dominated six days of the week; the institution dominated one day of the week. It’s clear from Kuyper’s thinking that Christians who separated on Sunday as each went to his own church could nevertheless fully participate in kingdom activities from Monday to Saturday, be it in joint Christian schools, a joint political party, joint labour associations, and so much more. Unity amongst Christians – and churches – had to lie on the organic level, not on the institutional level.

SCHILDER ON CHURCH

In response to efforts to absolutize Kuyper’s positions, Schilder dug into Scripture to evaluate whether Kuyper’s understandings were in fact what the Lord had revealed. As indicated, he used the writings of notable churchmen of the past as well as the confessions of the church to come to his positions.

He argued that Scripture nowhere teaches that there are two churches, one visible only to God and the other visible to people. He certainly granted that there are invisible aspects to the church, for example the faith in the members’ hearts, their prayers-in-secret, and their private expressions of love for one another (be it in the form of admonitions or in the form of financial assistance). But invisible aspects of the church do not make a church invisible any more than invisible aspects of a person (think of one’s soul) make the person invisible. Similarly, the fact that there are hypocrites in the church does not mean there’s an invisible church beside the church you see, any more than the presence of choir members who come for less than honourable motives (from the conductor’s perspective, e.g., to impress a girl; this is Kuyper’s example [iii]) means there’s an invisible choir. Scripture, Schilder insisted, teaches the existence of one church, and that’s also how the confessions speak. We join the church of the Lord by very physically congregating with the saints, placing ourselves humbly under the under the oversight of the office bearers, and being a living member of the church. In similar fashion he argued that Scripture does not know Kuyper’s distinction between church as organism and church as institution. [iv]

In place of the weaknesses he saw in Kuyper’s ecclesiology, Schilder resurrected a doctrine concerning the church that went back in largest part to the teachings of the great Reformers and was reflected in the three Forms of Unity. [v] He emphasized that from heaven the ascended Christ is still in the process of gathering his church. Christ does that through the powerful working of his Word by his Spirit Sunday by Sunday, the fruit of which becomes evident through the week wherever believers receive their place in God’s wide world. Since Christ is still gathering his church through the preaching, it remains necessary to distinguish between a true church and a false church, that is to say where the Word of God has final authority versus where that Word does not have final authority. People are obligated to work along with Christ in his church gathering work in the sense that they need to make it their business to be gathered where the Word is faithfully proclaimed and maintained. As churches are grounded on the clear word alone, there ought not to be multiple churches in a given community; instead, church that treasure the Word of God ought to work towards unity. That’s even more so for churches with identical confessions (say, the Three Forms of Unity). Biblically speaking they may not co-exist comfortably side by side; they need to unite in one federation. In fact, Schilder went so far as to say that the will to unity was actually a vital mark of a true church.

SCHILDER IN TROUBLE

Schilder’s writings on topics like the church in De Reformatie found their way into many homes – and were received by many readers as a breath of fresh air. Instead of defending philosophically founded distinctions not found in Scripture or in the confessions, his readers perceived that this man kept going back to the Bible and using the writings of esteemed church fathers to show that what he found in Scripture was by no means novel. For many who respected the Bible and appreciated church history, this was invigorating. These people esteemed Schilder highly and thanked God for him.

With the coming of the Second World War in the Netherlands in 1939, invading Nazis forced the suspension of the publication of De Reformatie. Schilder himself was compelled to go into hiding to escape extradition to a German labour camp. Despite the war, however, a General Synod of the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands was convened in 1939 (it continued till 1942). On the agenda was the effort to vindicate Kuyper’s teaching (on various subjects, including common grace, presumptive regeneration, the pluriformity of the church, and more). Synod made specific determinations on the subject of presumptive regeneration (see the earlier Clarion article). A subsequent synod (begun in 1943) demanded that all the churches agree with those conclusions – Schilder included. Schilder could not in good conscience do so; instead, he begged Synod to wait with finalizing their doctrinal statements till after the war (thus giving time for cooler heads to prevail). Synod, however, insisted on Schilder’s immediate acquiescence to its statements. Since Schilder could not do that (he was also all the while in hiding!), Synod summarily suspended him on March 23, 1944, from his position as professor in the church’s seminary in Kampen as well as from his status as minister in the churches. As Schilder did not “repent”, Synod deposed him three months later.

LIBERATION

News of his suspension came as a shock to many in the churches. They knew from his writing that Schilder was a man of the Word who loved the Lord and the church of the Lord. They could not understand how the General Synod could find fault with this man of God. To many in the churches, his suspension and deposition were grossly unfair and a wicked abuse of authority.

As church members read the material Synod wanted them to agree to, many protested that they could not in good conscience do so as that material bound them beyond Scripture and confessions. As a result, Synod deposed these office bearers too and even placed whole consistories and churches outside the federation.

What now was to become of those members (and some churches) on the receiving end of Synod’s heavy-handedness? On August 11, 1944, a meeting was held in The Hague to which were invited all those who were unhappy with Synod’s work. The response was enormous. The featured speaker turned out to be Dr. Klaas Schilder himself, who took the risk of coming out of hiding for the occasion. He had penned – and now read out – an Act of Liberation and Return, expressing liberation from the Synod’s tyranny and return to the truth and freedom of Scripture and confessions.

The first synod of the newly Liberated churches in 1945 decided to establish a scripturally faithful seminary, to which Dr K. Schilder was appointed to teaching in the field of dogmatics.

THE CHURCH – KEY ELEMENTS

I started this article saying that immigrants who formed the CanRC came with some fixed elements in their ecclesiology, formed in large part in the crucible known as the Liberation of 1944. We can now list some of these distinctives (in no order of importance):

- A high regard for scriptural instruction and allegiance to the Three Forms of Unity – with no place for binding to documents beyond these. Churches thus aligned were “true churches” with whom unity was to be pursued.

- A conviction that the church is the Lord’s work as he gathers (present progressive tense, meaning ongoing work) his people. People were duty-bound to work along with God and so gather themselves wherever he was already gathering.

- A disdain for philosophical and scholastic constructions such as invisible vs. visible, organic vs. institutional, militant vs. triumphant, and the doctrine of pluriformity.

- An aversion against that form of church polity where the broadest assembly (the general synod) is seen as having the authority to set its own agenda or even discipline office bearers or members of local churches. Instead, the immigrants were convinced that the Lord had given authority to the elders and hence to the consistory of the local church.

- There ought not to be multiple (true) churches in a given community. As there is one truth and one gospel proclaimed from faithful pulpits, true churches ought to display the will to unity with other true churches.

Clarence Bouwman, minister emeritus, Smithville Canadian Reformed Church

Convictions such as these led the first immigrants to strive to join church federations already existing in the new world (i.e., the Christian Reformed Church or Protestant Reformed Churches). [vi] When these newcomers saw no option but to establish a new federation of churches, their initial synod decisions grew out of these distinctives. But that’s a story for another article.

[i] C Bouwman, “Why are we Canadian Reformed?”, Clarion, 12 June 2020, Vol. 60 Number 12, pp. 333.

[ii] Our Worship (trans. Harry Boonstra, et al).

[iii] D. Deddens, Cursus bij Kaarslicht: Lezingen van Klaas Schilder in de laatste oorlogs-winter, Vol. 1, p. 23.

[iv] For a very readable introduction to Schilder’s thoughts about pluriformity, see his article on the subject in The Klaas Schilder Reader: the Essential Theological Writings, p. 90 ff.

[v] See J. M. Batteau, “Schilder on the Church”, in Always Obedient: Essays on the Teachings of Dr Klaas Schilder, Ed J. Geertsema (Phillipsburg: P & R Publishing, 1995), 65-100.

[vi] See the earlier quoted Clarion article in Vol. 69, Number 12, pg 333-336.