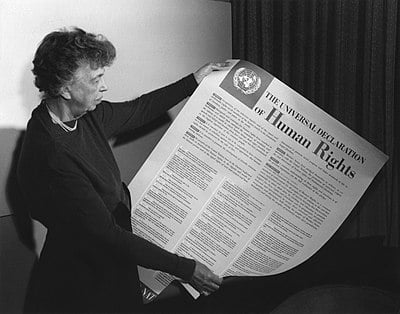

Human rights are relatively new. It was only following the atrocities of WW II that human rights became a global movement. Already after WW I the League of Nations attempted to protect human rights. Its efforts failed though, as it couldn’t enforce its decisions. In 1941, President Roosevelt delivered a speech in which he advocated four fundamental freedoms: freedom of speech and religion, and freedom from poverty and fear. At the end of WW II, the United Nations was established, and in 1948 it adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Many countries incorporated the UDHR in their constitutions. Today, non-government organisations play a significant role in the maintenance of human rights. They raise awareness of human rights abuses and hold protests to pressure change.

Human rights are considered something that all people deserve because of who they are – humans. They are:

- Universal (applying to all people)

- Inalienable (they cannot be removed forcibly or voluntarily)

- Inherent (we are born with them)

- Indivisible (all rights are equally important).

Rights entitle us to freedoms. For example, we are born with the right to liberty, which gives us freedom of speech.

As Christians, we must understand human rights correctly. If we are going to accept them, we must be able to find support for them in Scripture.

At face value, there may seem nothing wrong with the notion of human rights. It is Biblical, after all, that one person may not murder another. It is Biblical to show kindness to the sick or helpless people. Perhaps most importantly, human rights have entitled us, as Christians, to freedoms which we would not have otherwise experienced, including freedom of religion, speech, and assembly. Scripture advocates justice.

Is the human rights movement then not the world catching up to the Bible?

No. Human rights are man-made and man-centred. Biblical justice, though, does not take its starting point in man, but in God.

The image of God

Many Christians will point to humans being in God’s image as a basis for human rights.

After the fall into sin, however, man completely lost the image of God. He didn’t lose his intellect or his humanness though, so what is the image of God then? Our catechism says, “God created man good and in His image, that is, in true righteousness and holiness” (HC, Q&A 6). The Belgic Confession talks about God’s image similarly: “after His own image and likeness, good, righteous, and holy” (BC, art. 14). Likewise, the Canons of Dort defines God’s image as being holy (CoD, Ch 3/4, art. 1). There is no way in which we can reflect God’s image by being rational and intelligent creatures – these are simply gifts to aid us in our office as God’s image-bearers. When we understand what it means to be in God’s image, we cannot use it as a foundation for human rights.

Those who argue that the image of God in man gives man inherent rights, often use Genesis 9:6 as a proof text:

Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man his blood shall be shed; for in the image of God He made man.

However, this text does not refer to man’s current state but to his original creation.

While it does not say that all men are still in God’s image, it does give a Biblical reason for protecting man’s life – his original status in creation. When someone commits murder, he is dishonouring God who created man in his image. This is why God forbids murder.

Furthermore, God demands that we love our neighbour. So we owe this obedience to God, but we don’t deserve each other’s love based on inherent rights.

Two different sets of values

When human rights seem to overlap with Biblical norms, they do so accidentally. Human rights rest on man’s corrupted sense of right and wrong, which he retained after the fall. Let us look at a few examples of how man’s sense of justice can conflict with Scripture.

Humans supposedly have the right to live. But the Bible says, “For the wages of sin is death, but the gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 6:23). The world says humans have the right to autonomy over their own body. The Bible says, “Or do you not know that your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, whom you have from God, and you are not your own?” (1 Cor. 6:19). Humans have the right to freedom from fear. But the Bible says, “But if you do evil, be afraid” (Rom. 13:4). Humans have the right to freedom from poverty. The Bible says, “If anyone will not work, neither shall he eat” (2 Thess. 3:10). Humans have the right to freedom of speech. The Bible says, “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain” and “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbour” (Ex. 20:7, 16). Humans have the right to freedom of choice. The Bible says, “I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose life.” (Deut. 30:19). These examples will suffice to show that at least some human rights entitle us to things that God does not – or at least not in every circumstance.

Not all human rights are wrong in the same way as the ones mentioned above in that they directly conflict with Scripture. Some human rights have positive outcomes, for example, the rights to life and equality before the law. But we owe this justice to God, not to man because of his rights.

What has to give way: the law or our freedoms?

Human rights are supposedly sovereign, but the Bible teaches differently.

Let us look at an example. A woman allegedly has the right to autonomy over her own body. At the same time, a baby has the right to live. So what happens when these two rights clash? What if a mother has the right to abort an unborn baby, and that baby has the right to live? The Bible does not have this issue because our freedoms do not originate from sovereign rights. Only God’s law is sovereign. It states, “you shall not murder” and “you shall love your neighbour.” The women’s freedoms are, therefore, anything within the framework of God’s law.

Under English tradition, Australia does not have a Bill of Rights. Instead, citizens are free to do as they please until they transgress the law. So in Australia, the law is sovereign. This is more Biblical since God’s law works similarly.

Picture this. George lives in the USA and has human rights. The world teaches that all his country’s legislation must be outside his sphere of rights. The Bible teaches that George has no sphere of rights. The USA’s government may make any legislation that does not conflict with God’s word. So in certain cases, it may put limits to George’s freedom of speech (as long as these limits do not conflict with Scripture). Of course, a government must do what’s best for its citizens (that falls under God’s command to love). But governments are only limited by God’s law, not by human rights.

Once again, we see that God’s law determines justice, not human rights.

Conclusion

So according to the Bible, we deserve death. God has granted us life, and this is to be respected by those around us. We must love our neighbour. It should not surprise us that many human rights contradict God’s Word. They are based entirely on man’s feeling of justice. To man, it doesn’t seem like the right thing for one person to kill another. So, it would only make sense to him if people had the right to justice. The only values that an atheist has must come from his corrupted light of nature. As a result, they are subject to his emotions and can change according to the situation. So here we see two systems of justice. The human rights system focuses on man and his rights. The Bible’s system focuses on God and His law. They sometimes seem to have the same result – justice – but that is coincidental, often depending on how much lawmakers in the west still have a Christian background.

We need clear discernment lest we confuse God’s law with human rights. The root cause of this shift of focus in our world today is that people no longer want to believe in God nor use His law as the standard for right and wrong. Consequently, they need to invent their own morals and their own system for upholding them. It may seem like a harmless change, but I want to highlight some of the problems and dangers of human-right-centred thinking.

- Human rights undermine the Bible’s teaching on human depravity.

- They promote humanism.

- They have been used to justify same-sex marriage, women in office, and abortion.

- Human rights movement condemns capital and corporal punishment. The Bible does not.

Human rights are the result of the subjective values of man, so let us hold onto the unchanging law of God as the absolute standard for justice instead.

(Johannes Retief is a Year 10 student at the John Calvin Christian College, Armadale)